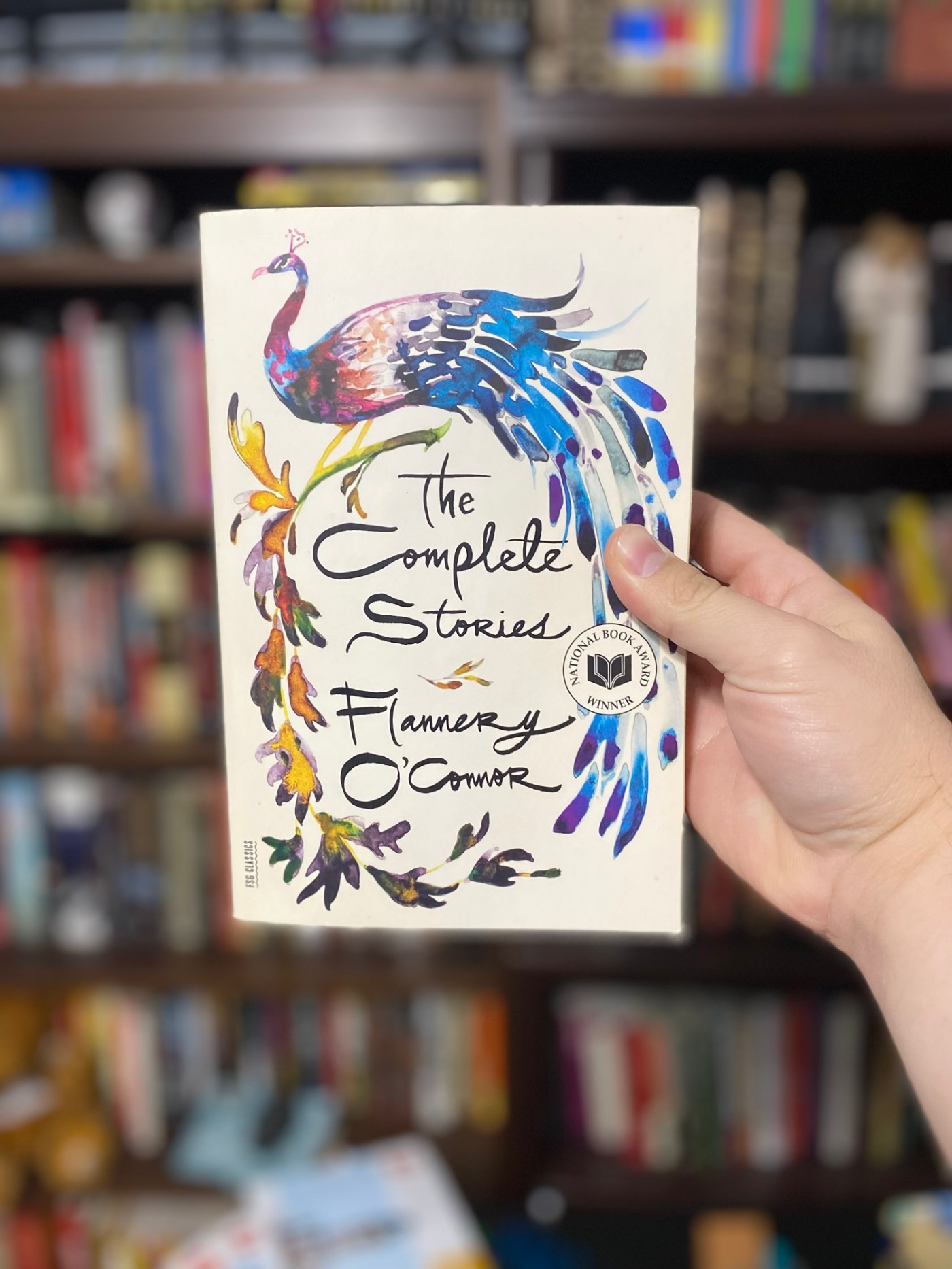

The book is The Complete Stories of Flannery O’Connor by Flannery O’Connor. These stories were written over the career of Ms. O’Connor’s career. This anthology was published in 1971. I started reading this a couple of years ago. A short story here and there. But I finished it in September of 2025.

The title of course refers to what the book is, the complete collection of all of Flannery O’Connor’s short stories.

I read this because I heard that O’Connor was an influence on Cormac McCarthy. I had read the story A Good Man is Hard to Find in college and loved it. Harold Bloom liked her work. I knew she was great but I hadn’t really dug into her work yet.

From what I understand O’Connor was a devout Catholic. From biographical stories I’ve heard of her it seems she was a believer. But a lot of her writing is critical or cynical about Christianity, at least the Christian culture of the deep south in the 30’s and 40’s. It was a hard time to be alive and if her writing is any indication, it was a time of a lot of fake, cultural Christianity full of charlotans and con-men. The villains are either faking their Christianity for personal gain or outright defiant of it. But there are no happy or content atheists in her work. O’Connor never gives a suggestion that atheism would lead to a more satisfying life. The message I get from her work is that life is hard for everyone and filled with more questions than answers. She seems well aware of how finite and faulty humans are.

There are sections like the following,

“Jesus died to redeem you,” she said. “I never ast Him,” he muttered. (p80)

There are a few scenes in her stories of people trying to evangelize and getting shut down or stumped by a non-believer. Why does O’Connor write scenes like this if she is a true believer? Maybe it’s because she herself cannot explain to anyone why she believes. Maybe it’s just as much a mystery to her as it is to the non-believing characters in her story. It’s hard to say.

Her prose is amazing.

“The lanterns gilded the leaves of the trees orange on the level where they hung and above them was black-green and below them were different dim muted colors that made the girls sitting at the table look prettier than they were.” (p242)

Such beautiful writing. Her plots are razor thin. A lot of her stories are just characters doing things or having things be done to them. There’s a beautiful chaos in the narrative. For example,

“He stood appalled, judging himself with the thoroughness of God, while the action of mercy covered his pride like a flame and consumed it. He had never thought himself a great sinner before but he saw now that his true depravity had been hidden from him lest it cause him despair. He realized that he was forgiven for sins from the beginning of time, when he had conceived in his own heart the sin of Adam, until the present, when he had denied poor Nelson. He saw that no sin was too monstrous for him to claim as his own, and since God loved in proportion as He forgave, he felt ready at that instant to enter Paradise.” (p269-270)

This comes from a story called The Artificial Nigger, about a man and his grandson taking a trip into the city for an appointment. The boy has never been to the big city before and is very excited. The grandfather is a country man and hates the city. He says it’s full of sinners and evil people. But then while they’re downtown the boy accidentally breaks a mannequin of a black man and it’s very embarrassing and people get mad at him. The boy looks to the grandfather for help but out of fear of the crowd the grandfather denies that he knows the boy and runs away, leaving the boy to the mercy of the angry downtown crowd. It’s an incredible moment. An allusion to Peter’s denial of Christ. The grandfather learns that he, an honest country man, is no better than any of the self-serving city folk. He sees the depths to which his sin can go and is astonished and ashamed.

But notice that last line. “He saw that no sin was too monstrous for him to claim as his own, and since God loved in proportion as He forgave, he felt ready at that instant to enter Paradise.”

O’Connor is highlighting the right biblical doctrine of God’s grace and throwing it into the face of the Christian reader as a challenge of belief. She’s pitting the heart against the head in making us examine how we naturally feel about the truth of God’s forgiveness. The grandfather has sinned deeply which means he is forgiven deeply, which means his soul has never been more ready for heaven.

It’s another grace of God that for most of our lives we don’t realize in our actions the true depravity of our sin. The average person believes himself to be generally an average sinner. But in stories like this the potential for human sin is revealed. We like to think we’re not capable of such appalling sin but in reality we are. Any person is capable of any sin, no matter how diabolical. We don’t appreciate enough the blessing it is that we do not actualize the potential for true wickedness of our sinful hearts.

In this story it’s fear that draws up the deep sin in the grandfather. That’s usually the case. Fear leads to sin. And it does generational damage. The grandfather isn’t the only one who realizes his sin. The boy witnesses it too and is forever jaded and embittered by it.

It’s an incredible story. That’s the talent of O’Connor, her ability to show the sin of humanity and the forgiveness of God in such a beautiful and heartbreaking way.

The characters in O’Connor’s short stories are all very honest. In them you see reality, with all its ugliness and cruelty. They feel like people maybe she knew in her life.

Her style is southern gothic with a touch of religious magical realism. Her characters talk about religion as if it’s something they all know but not everyone truly believes. It’s a lifestyle or a way of life in which everyone participates to some degree. There are families and drifters. Mothers. Sons and daughters.

O’Connor paints a realistic detailed picture of the poor South. What a terrible time and place to be alive. The characters feel trapped in their culture. I can’t recall any true believers. The character that comes the closest is The Misfit in the story A Good Man is Hard to Find. He’s a killer and a villain but then he says something profound.

“Jesus was the only One that ever raised the dead.” The Misfit continued, “and He shouldn’t have done it. He thrown everything off balance. If He did what He said, then it’s nothing for you to do but throw away everything and follow Him, and if He didn’t, then it’s nothing for you to do but enjoy the few minutes you got left the best way you can—by killing somebody or burning down his house or doing some other meanness to him. No pleasure but meanness,” he said and his voice had become almost a snarl. (p132)

It’s an honest counting of the cost to be a follower of Christ. This is from a story called A Good Man is Hard to Find. The Misfit, sinner and killer that he is, realizes the complete life-changing power of the gospel and he rejects. But he at least recognizes it for the power that it is. This shows that no matter how much knowledge or intellectual understanding one might have of the gospel, that mental ascension doesn’t save. Without repentance and submission to Christ there is no salvation. Cognitive understanding isn’t enough. The sad thing is that most honest faithful Christians don’t understand that Christ is Lord of all. It’s not just a personal relationship with Jesus, it’s a complete surrender.

O’Connor’s stories are simple and easy to follow in context but in theme and message, there are many layers to unpack. Those are the best kind of stories. At first glance there’s not a lot going on between the characters but when you start to think about it, there is so much more going on in the action and dialogue.

The feeling and tone of O’Connor’s stories can be morbid and grim. Taken at face-value they can be depressing. But they’re so beautifully written and there are hidden depths.

I highly recommend these O’Connor’s stories to anyone who loves modern American literature. If you love simple stories that make you think, this is the collection for you.

***********************************************

Quotations

“You got a secret need,” the blind man said. “Them that know Jesus once can’t escape Him in the end.” -“I ain’t never known Him,” Haze said “You got a least knowledge,” the blind man said. “That’s enough. You know His name and you’re marked. If Jesus has marked you there ain’t nothing you can do about it. Them that have knowledge can’t swap it for ignorance.” (p72)

“”””

She sent the child away and it come back and she sent it away again and it come back again and ever time she sent it away it come back to where her and this man was living in Sin. They strangled it with a silk stocking and hung it up in the chimney. It didn’t give her any peace after that, though. Everything she looked at was that child. Jesus made it beautiful to haunt her. (p73)

“”””

“What you seen?” she said, using the same tone of voice all the time. She hit him across the legs with the stick, but he was like part of the tree. “Jesus died to redeem you,” she said. “I never ast Him,” he muttered. (p80)

“”””

“A good man is hard to find,” Red Sammy said. “Everything is getting terrible. I remember the day you could go off and leave your screen door unlatched. Not no more.” (p122)

“”””

I call myself The Misfit,” he said, “because I can’t make what all I done wrong fit what all I gone through in punishment.” (p131)

“”””

“Jesus was the only One that ever raised the dead.” The Misfit continued, “and He shouldn’t have done it. He thrown everything off balance. If He did what He said, then it’s nothing for you to do but throw away everything and follow Him, and if He didn’t, then it’s nothing for you to do but enjoy the few minutes you got left the best way you can—by killing somebody or burning down his house or doing some other meanness to him. No pleasure but meanness,” he said and his voice had become almost a snarl. (p132)

“”””

He seemed to be a young man but he had a look of composed dissatisfaction as if he understood life thoroughly. (p146)

“”””

A nigger thinks anybody is rich he can steal from and that white trash thinks anybody is rich who can afford to hire people as sorry as they are. And all I’ve got is the dirt under my feet!” (p203)

“”””

“They’re only farm boys. These girls would turn up their noses at them.” “Huh,” the child said. “They wear pants. They’re sixteen and they got a car. Somebody said they were both going to be Church of God preachers because you don’t have to know nothing to be one.” (p239)

“”””

The lanterns gilded the leaves of the trees orange on the level where they hung and above them was black-green and below them were different dim muted colors that made the girls sitting at the table look prettier than they were. (p242)

“”””

His face in the waning afternoon light looked ravaged and abandoned. He could feel the boy’s steady hate, traveling at an even pace behind him and he knew that (if by some miracle they escaped being murdered in the city) it would continue just that way for the rest of his life. He knew that now he was wandering into a black strange place where nothing was like it had ever been before, a long old age without respect and an end that would be welcome because it would be the end. (p267)

“”””

He stood appalled, judging himself with the thoroughness of God, while the action of mercy covered his pride like a flame and consumed it. He had never thought himself a great sinner before but he saw now that his true depravity had been hidden from him lest it cause him despair. He realized that he was forgiven for sins from the beginning of time, when he had conceived in his own heart the sin of Adam, until the present, when he had denied poor Nelson. He saw that no sin was too monstrous for him to claim as his own, and since God loved in proportion as He forgave, he felt ready at that instant to enter Paradise. (p269-270)

“”””

You could say, “My daughter is a nurse,” or “My daughter is a schoolteacher,” or even, “My daughter is a chemical engineer.” You could not say, “My daughter is a philosopher.” That was something that had ended with the Greeks and Romans. (p276)

“”””

We know it by wishing to know nothing of Nothing.” These words had been underlined with a blue pencil and they worked on Mrs. Hopewell like some evil incantation in gibberish. She shut the book quickly and went out of the room as if she were having a chill. (p277)

“””””

“Its just as well you don’t understand,” and she pulls him by the neck, face-down, against her. “We are all damned,” said, “but some of us have taken off our blindfolds and see that there’s nothing to see. It’s a kind of salvation.” (p288)

“”””

He knew the old man was dead without touching him and he continued to sit across the table from the corpse, finishing his breakfast in a kind of sullen embarrassment, as if he were in the presence of a new personality and couldn’t think of anything to say. Finally he said in a querulous tone, “Just hold your horses. I already told you I would do it right.” The voice sounded like a stranger’s voice, as if the death had changed him instead of the old man. (p294-295)

“”””

She was a good Christian woman with a large respect for religion, though she did not, of course, believe any of it was true. (p316)

“”””

She knew that if he would get in there now, or get out and fix fences, or do any kind of work-real work, not writing that he might avoid this nervous breakdown. (p361)

“”””

Thomas loved his mother. He loved her because it was his nature to do so, but there were times when he could not endure her love for him. (p385)

“”””

Julian could feel the rage in her at having no weapon like his mother’s smile. (p417)

“”””

The sky was bone-white and the slick highway stretched before them like a piece of the earth’s exposed nerve. (p443)

“”””

“I ain’t asked for no explanation,” he said. “I already know why I do what I do.” “Well good!” Sheppard said. “Suppose you tell me what’s made you do the things you’ve done?” A black sheen appeared in the boy’s eyes. “Satan,” he said. “He has me in his power.” (p450)

“”””

The next year he quit school because he was sixteen and could. He went to the trade school for a while, then he quit the trade school and worked for six months in a garage. The only reason he worked at all was to pay for more tattoos. (p513)

“”””

Long views depressed Parker. You look out into space like that and you begin to feel as if someone were after you, the navy or the government or religion. (p516)

“”””

Parker returned to the picture-the haloed head of a flat stern Byzantine Christ with all-demanding eyes. He sat there trembling; his heart began slowly to beat again as if it were being brought to life by a subtle power. (p522)

Leave a comment