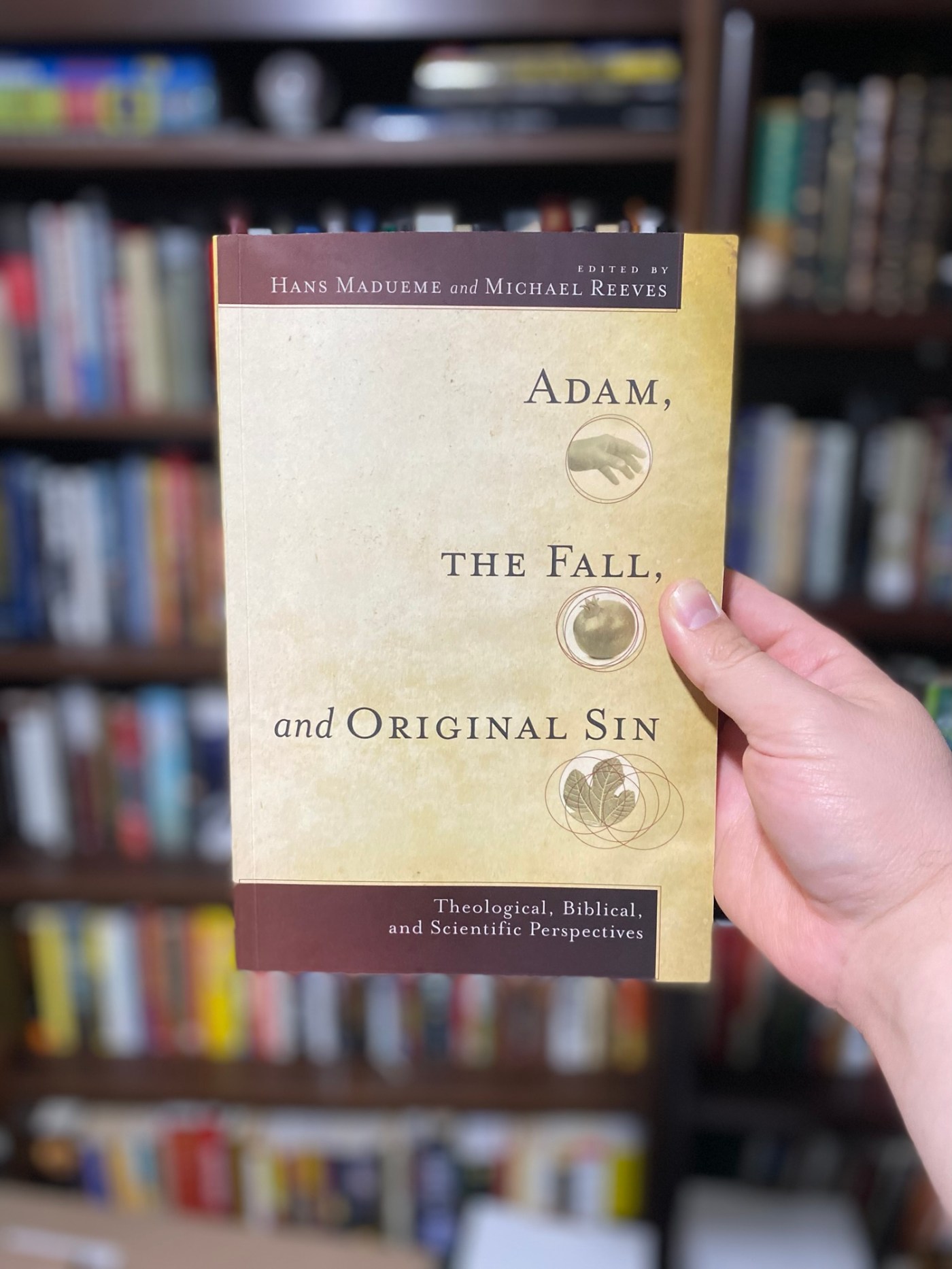

The book is Adam, The Fall, and Original Sin edited by Hans Madueme and Michael Reeves. It was originally published in 2014 by Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group. I read the 2014 paperback edition. I read it in February of 2025.

The title refers to the topic of the book. This is a collection of essays written by various academics and theologians exploring the topic of the literal Adam and Eve, the garden of Eden, the Fall and original sin. Should we take Genesis and the creation story literally? Were Adam and Eve literal people in our real historical human timeline? What about evolution? What is sin and where did it come from? Where is the garden of Eden now? I’m researching these questions in hopes to write a book someday about this topic.

We often talk about non-negotiables of the Christian faith. The divinity of Christ, the trinity, the virgin birth, the sinlessness of Christ, the resurrection. These are all deal breakers in terms of what is considered true Christianity. It’s how we differentiate between Protestant and Catholic, Christian and Mormon, biblical faithfulness and heresy.

One non-negotiable that I don’t see discussed nearly enough is the truth of creation versus evolution.

I saw an interview with Tom Holland (the historian, not Spider-Man) and the person interviewing him was a Christian and he was talking to Holland about his book Dominion which is all about how Christianity has changed the entire world to the point that everything we see and hear and think is Christian. Holland talks about how the way we measure time itself is Christian. History is literally hinged on the birth of Jesus Christ. Holland claims “All of us in the West are a goldfish, and the water that we swim in is Christianity.” He has also related it to Chernobyl. The same way Chernobyl spread radiation in the air to the point that everything there is contaminated with radiation and they don’t even realize it, that is Western civilization with Christianity. It’s clear that Holland has a lot of affection for Christianity and sees it as the bulwark against fascist tyranny and the authoritarianism of the barbaric past. The Christian interviewing Holland asked him why he doesn’t consider himself a true converted faithful Christian, and Holland said, it’s the dinosaur problem. He cannot reconcile the Christianity of the Bible with evolution and what the scientific community says about our origins.

I think in this regard, Tom Holland speaks for millions of people who see the net benefit that Christianity has been on the world, but just cannot bring themselves to real believing faith because of the conclusions from modern science about the origins of life.

It’s one of the main stumbling blocks for people coming to Christ. They read the creation story and they say it’s a beautiful metaphor or symbolism but it just doesn’t match up with what they read in a modern science textbook.

I actually have more respect for people like Tom Holland and Jordan Peterson who have counted the cost and have decided they cannot pay the price. Too many people simply say a prayer and think they’re Christians, when in actuality they carry many beliefs that deny the Christ they claim to follow.

In Matthew 19:4 Jesus appeals to God as the creator of male and female from the beginning. “He answered, “Have you not read that he who created them from the beginning made them male and female,” (Matt 19:4).

Wouldn’t Jesus know the truth about the origins of men and women and the beginning of the world? He calls God “he who created them.” When he asks “have you not read” he’s talking about the book of Genesis. So clearly Jesus believes the Genesis account and takes it literally in regards to God’s creation of men and women, they being the first man Adam and the first woman Eve. Are we allowed to disagree with Jesus’ own words about creation? This is what’s at stake when we stray from a literal belief in Adam and Eve.

This issue is not isolated to only Adam and Eve. Anyone who denies that Adam and Eve were literal figures in our human history are burdened with the task of explaining who exactly was the first person and why. The Bible has a long list of names of people from Adam to Jesus. Are these genealogies incorrect? Who was the first real person? Were Cain and Abel real? What about Seth? Enoch? Methuselah? Noah? They all trace back directly to Adam and Eve. Are we going to deny the existence of all of these people?

The first eleven chapters of Genesis are called “primeval history.” Basically everything before the calling of Abraham. The Garden of Eden, the Flood, the Tower of Babel. All the weird stuff. (Not to say that there isn’t more weird stuff throughout the Bible but all the really weird stuff like the Nephilim is in the first eleven chapters). That’s all before Abraham and considered primeval history. Everything from Abraham on is called ancestral history. Abraham was the first of God’s chosen people. It wasn’t until Abraham that God said he will set apart a distinct people for himself. They have the promise of salvation through Christ. This is when the ancestry of the Jewish people technically starts so Abraham is commonly considered the first principle character who is a historically documented figure in the Bible. By historically documented they mean non-biblical documentation. Why the Bible is not considered a reliable historical document is beyond me but I digress.

As I’ve mentioned before, this mindset comes at a larger cost than most people realize. The cost of disregarding Adam and Eve as historical figures is first to deny Jesus’ own words about God creating men and women. Second, it then requires you to come up with some other origin of sin and death. If the garden and the serpent are not real then where did sin and pain come from? Pain and death are undeniably real. If the story of the garden of Eden was a metaphor or symbol for something then what is it a symbol for? Where did sin come from?

What is sin? Did it evolve in us? Is it a psychological condition? Is it a feeling? If we go down that path then it gets really dangerous for the Christian worldview. What did Christ’s work on the cross accomplish? Jesus mission was to redeem us from our sins. If sin is something akin to an evolved mental or emotional state then why did Christ need to come and die on the cross to remove it? When we diminish the reality of what sin is, we diminish Christ’s work to remove it. That’s exactly what happens when we deny the reality of the Garden of Eden. It’s the story of how sin, pain, and death entered the world therefore it is as real as sin, pain, and death. If human suffering is real (and who could possibly argue it’s not) then it must have an origin story.

“Sin came into the world through one man,” Paul summarizes in Romans 5:12

Paul’s soteriology, Christology, theological anthropology, and hamartiology come together in these ten terse verses, none of which is intelligible without Adam in his historical existence and real aftereffects, which Christ came to address and remedy.” (p42-43)

These are the questions that this book explores. As it’s a collection of essays and papers from academia, it was eclectic and therefore not very helpful. If it was one work by one author it might have been more cohesive.

This collection of essays was in favor of seeing Adam and Eve as historical figures. There was one chapter about the evolution of Neanderthal and homo erectus that was interesting. They questioned the methods of determining the evolution of the brain.

“We can conclude that it is very difficult to make connections between brain size, brain structure, and cognitive abilities in general or specific capabilities. It therefore seems more fruitful to rely on the archaeological record tor indications of intelligence and complex behaviors.” (p70)

My main takeaway is that there are many more books I need to read. I’m currently deep diving into this topic and the research is out there. I look forward to investigating it further.

The more I dig into this the more crucial it becomes to solve this as a close-handed issue.

While being a collection of academic works, it stayed approachable to the layman.

I highly recommend this book. It’s a good introduction to a deeper issue that no one is talking about. This is an important book that every Christian should read if for nothing more than to start considering the questions it raises about what we truly believe about the Bible.

****************************************************

Notable Quotables

“”””

Genesis 2:5 says “there was no man (‘adam) to work the ground,” and thus in 2:7 the Lord God formed “the man” using dust from the ground. In 2:18 “the man” is alone, and the Lord God sets out to make a helper fit for him. Throughout 2:4-4:26, whether he is called “the man” or “Adam,” he is presented as one person. (p14)

“”””

The genealogies of Genesis 1-11 link Father Abraham, whom the people of Israel took to be historical, with Adam, who is otherwise hidden from the Israelites in the mists of antiquity. (p15)

“”””

And what shall we make of the “death” that God threatens in Genesis 2:17? I maintain that the primary reference is “spiritual death” (alienation from God and one another) as exhibited in Genesis 3:8-13. But that is not all: it would appear that this is followed by their physical death as well (v. 19). For now I simply observe that we should be careful about letting the distinction between spiritual and physical death, which is proper, lead us to drive a wedge of separation between the two kinds of death: it looks like the author presents them as two aspects of one experience. (p18)

“”””

we perceive the firm footing of the Jewish and New Testament interpretive tradition that sees the Evil One (“Satan” or “the devil”) as the agent who used this serpent as its mouthpiece (e.g., Wis. 1:13; 2:24; John 8:44; Rev. 12:9; 20:2). In fact, to deny this by insisting that Genesis never mentions the Evil One is actually a poor reading, because it Fails to appreciate “showing” over “telling.” If we read the story thus poorly we miss a crucial part of its import. (p19)

“”””

In Proverbs 3:18; 11:30; 13:12; 15:4, various blessings are likened to a tree of life: all of these blessings, according to Proverbs, are means to keep the faithful on the path to everlasting happiness. In Revelation 2:7; 22:2, 14, 19, the tree is a symbol of confirmation in holiness for the faithful. This warrants us in finding this tree to be some kind of “sacrament” that sustains or confirms someone in his moral condition: that is why God finds it so horrifying to think of the man eating of the tree in his current state. I call it a “sacrament” because I do not know how it is supposed to convey its effects, any more than I know how the biblical sacrifices, or the washing ceremonies, or baptism, or the Lord’s Supper work. But they do work. Only in this sense may the tree be called “magic,” but this sense has moved us away from folklore.” (p20-21)

“”””

That is, Ezekiel has a “fall story” based on Genesis 3.

And when the prophet says that his addressee was “an anointed guardian cherub,” we can recognize that we are reading imagery here, not a literal description. The point is that “the extravagant pretensions of Tyre are graphically and poetically portrayed… along with the utter devastation inflicted upon Tyre as a consequence.” The rhetorical power derives from reading Genesis 3 as a fall story; there would be no such power in another reading. 66 Another likely echo of Genesis-3-read-as-a-fall-story is Ecclesiastes 7:29: “See, this alone I found, that God made man [Hebrew ha-‘ adam, humankind] upright, but they [Hebrew hémmâ] have sought out many schemes.” (p25)

“”””

as D. Callender Jr. points out: “The assumption that Adam was an actual historical figure persisted largely unchallenged in the Christian West until the development of modern literary criticism and the rise of biological evolutionism.” (p38)

“”””

Adam is central to Paul’s soteriological understanding. Romans 5:14, which explicitly mentions Adam twice, is key in a literary unit that explains justification and reconciliation, two of Paul’s most fundamental soteriological categories. Justification is mentioned in Romans 5:1 and 9, indicating this is a major theme of the chapter. (p42)

“”””

“Sin came into the world through one man,” Paul summarizes in Romans 5:12

Paul’s soteriology, Christology, theological anthropology, and hamartiology come together in these ten terse verses, none of which is intelligible without Adam in his historical existence and real aftereffects, which Christ came to address and remedy. (p42-43)

“”””

consensus among paleoanthropologists is that there are enough similarities between earlier hominins and early species in the genus Homo to accept the hypothesis that these earlier hominins were ancestral to humans.” (p61)

“”””

But although (relative) size matters, it is not the only variable determining cognitive capacities. * Brain organization may be a more reliable indicator of intelligence than brain size. A long-standing controversy exists between researchers who argue that brain reorganization from an apelike structure to a humanlike organization was already under way in the australopithecines and researchers holding the view that the australopithecine brain is essentially apelike, with modern features first manifesting themselves in early species of Homo. ” We can conclude that it is very difficult to make connections between brain size, brain structure, and cognitive abilities in general or specific capabilities. It therefore seems more fruitful to rely on the archaeological record tor indications of intelligence and complex behaviors. (p70)

“”””

When Homo ergaster enters the scene, use of technology becomes more complex and planned. Evidence for symbolic behavior is not synchronous with the appearance of anatomically modern humans, and some indications of advanced cognition also occur earlier in the archaeological record. The fossil and archaeological records can therefore be seen to support a clear difference between the australopithecines and Homo.’ Researchers working from a Christian perspective have mostly drawn the line between human and nonhuman at exactly this juncture,” and the recent evidence presented above tends to strengthen rather than erode this position. Paleoanthropologists overstate their case when they claim that the evidence unequivocally supports the idea that the australopithecines were the ancestors of the Homo lineage. Even when we take the imperfection of the fossil and archaeological record into account, the fact remains that in several crucial respects, the australopithecines were very different from us. (p77)

“”””

The differences between earlier and later species of the genus Homo are mainly in cranial traits and evidence for behavioral characteristics. As we have seen, the interpretation of many of these differences is surrounded by difficulties. Do they amount to differences at the level of a biological species? Recent evidence for interbreeding between modern humans and Neanderthals and Denisovans indicates that these “species” were not fully separated genetically, even if present thinking is they were rarely in contact for some 150,000 years. But even if the fossil species do represent real biological species, this is not problematic in the light of the biblical account of Adam, as long as he is the father of all such species. ‘** After all, the fall affected all Adam and Eve’s descendants, and Christ offers redemption to all humans who trust in his death and resurrection. (p79)

“”””

Without original sin, the Pelagian outlook on life was based on Stoic assumptions. People were viewed as primarily rational, willing, choosing beings. To avoid sin one must simply resolve to choose virtue. Godliness was a matter of grit and determination. (p98)

“”””

By the time he wrote City of God, Augustine had replaced his spiritual reading with a focus on redemptive-historical narrative. It is striking that throughout all these stages of development, Augustine believed Adam was a literal, historical figure.

Adam was as real a person as Jesus, and the original sin Adam wrought was as genuine as the corresponding salvation from Christ.

He perceived the architectonic connections between doctrines and knew that had Adam not been a historical person, then the reality of original sin, which shaped God’s grace and its reception, would collapse.

The nature of salvation offered through the second Adam is inextricably tied to the historicity of Adam. (p106-107)

“”””

Trust constitutes the very heart of humanity. Therefore, rejection of God’s Word lay at the heart of human sin; it was the original sin that originated all other sins. The original sin was the doubt Adam and Eve displayed in their denial of the truth and reliability of God’s Word in the command not to eat (Gen. 3:1-7). (p113)

“”””

their Maker and brought him immense satisfaction. Sin, therefore, was not of the essence of their nature (otherwise Christ could never have taken it), but a perversion of it. This concern to distance God from human sin is clearly apparent in Calvin’s writing. Commenting on Paul’s statement that we are by nature children of wrath (Eph. 2:3), Calvin writes, “Paul does not mean ‘nature” as it was established by God, but as it was vitiated in Adam. For it would be most unfitting for God to be made the author of death. Therefore, Adam so corrupted himself that infection spread from him to all his descendants.” (p130-131)

“”””

Reformed theologians have tended to be creationists, holding that each soul originates in an immediate and direct creative act of God. It is one thing to argue that God creates the soul without original righteousness: the suggestion that he creates it corrupt takes us to another level. Quite apart from the moral issues it raises, it faces a serious logical problem. As Robert Dabney points out, 4 it represents all humans as having, for a moment at least, an independent personal existence in innocence until they are “depraved” by an act of God in retribution for the imputed guilt of Adam’s sin. But there can be no such moment. We are conceived in guiltiness and sin: sinful from our first beginning (Ps. 51:5). We have no existence, even theoretically, except as depraved beings, and we come under no condemnation except as depraved beings. (p143)

“”””

This in turn leads him to make explicit his understanding of God: God is the common good of humanity? There is no “God out there” for Rauschenbusch, at least not in any sense that is meaningful or relevant for humans and thus for their theology. God is to be identified with society as it is properly ordered in terms of its common good. The heir of Hegel and German idealism, Rauschenbusch effectively identifies God with the goal of human history? (p174)

“”””

the biblical narrative of Eden, which Barth himself categorizes as saga.

We miss the unprecedented and incomparable thing which the Genesis passages tell us of the coming into being and existence of Adam if we try to read and understand it as history, relating it either favourably or unfavourably to scientific palzontology, or to what we now know with some historical certainty concerning the oldest and

most primitive forms of human life. The saga as a form of historical narration is a genre apart.

Saga in general is the form which, using intuition and imagination, has to take up historical narration at the point where events are no longer susceptible as such of historical proof.

Barth explicitly rejects any notion that there was ever a point in time where creation was unfallen. (p176-177)

“”””

all of them repudiate any notion that humanity stands guilty before God because of the imputation of an alien guilt, the guilt of a historical man called Adam, to all of his descendants. By the standards of Enlightenment thought, such an imputation would be unethical. (p183)

“”””

there is no movement from innocence to guilt and condemnation in history. Creation was imperfect from the beginning. That , has clear implications not only for how one understands the first chapters of Genesis (and, indeed, the trajectory of the drama of Genesis beyond chapte 3) but also for one’s understanding of the doctrine of God

Bultmann and Barth both employ the rhetoric about the seriousness of sin and the judgment of God but it is hard to square this with their view that creation was itself defective and fallen. In the traditional Christian orthodoxy, sin is an action that is a personal affront to a holy and righteous God, and it is that precisely because it involves a perversion of nature as he intended it to be and, indeed, as he created it to be.

If it is unethical to hold me to account for the action of a primeval ancestor, then why is it morally preferable that I be held responsible for my sin if that is indeed simply the result of my status at birth, of me being merely a human creature? What does it mean to say that I am responsible as an individual for my sinful state when it is actually a structural part of the original creation? And this, of course, has implications for how one understands redemption, implications that lie beyond the scope of this essay.”

One’s views of the historicity of Adam inevitably stand in positive connection to one’s view of creation, to whether there was a fall in history or whether sin/alienation from God is part of the natural order. The nature and status of Adam are foundational to one’s understanding of biblical theology. (p184-185)

“”””

No explanation needs to be offered about how Cain became someone who could murder his brother. The explanation has been given: Adam and Eve ate of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, bringing sin and death into the world (see Rom. S:12).

The reader goes from “very good” in Genesis 1:31 to “only evil continually” in 6:5, and in between is Adam’s sin in 3:1-7. Should not the reader conclude that the sin of Genesis 3 has resulted in the change from “very good” to “only evil continually”? Is the other option to leave the question of how things went from good to evil unexplored? The narrator does not have to tell his audience that the transition point was the sin of Adam. He has shown them. (p192-193)

“”””

When David, for instance, speaks of being “blameless” in Psalm 19:13, he does not refer to sinless perfection but to being “innocent of great transgression.” In the previous verse David asks to be declared “innocent from hidden faults,” so he is clearly not speaking of sinless perfection (Ps. 19:12). (p196)

“”””

What of Enns’s suggestion that there is no hint that Adam’s disobedience is the cause of the universal wickedness at the time of the flood? The chapter that precedes Genesis 6 is punctuated by the refrain “and he died” (Gen. 5:5, 8, 11, 14, 17, 20, 26, 31). What does the narrative provide as the explanation for all this dying? Death was threatened in 2:17 and announced in 3:19. Genesis teaches that people die because Adam sinned. Does Noah somehow escape this? The end of the account of Noah in Genesis 9:28-29 reads very much like the life-summaries in Genesis 5, and like them it ends with the words “and he died” (9:29). It seems to me that when it comes to hearing the song Moses sings in Genesis, Enns is tone-deaf. (p197)

“”””

All humans sin because all humans have been tragically affected by Adam’s fall. No humans escape the inclination to choose evil. No humans live in a world uncursed because of Adam’s sin.

Jeremiah asks in 13:23, “Can the Ethiopian change his skin or the leopard his spots? Then also you can do good who are accustomed to do evil.” He then asserts in 17:1, “The sin of Judah is written with a pen of iron; with a point of diamond it is engraved on the tablet of their heart,” writing a few verses later in 17:9, “The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately sick; who can understand it?”

Why would Israel be unable to see the goodness and truth of God’s word? Why would their confirmation in evil ways be likened to an Ethiopian being unable to change his skin color? (p200-201)

“”””

if sin is something superficial, something I simply opt into, then my need for grace is equally superficial. Such a view assumes that my will and my choice stand before all things, both sin and grace. (p218)

“”””

As other authors in this volume have argued, however, such attempts to eradicate the fall present a massive problem for theodicy. Sin’s origin in the world must be traceable to an earlier free choice of one of God’s creatures. Otherwise good and evil are eternal coprinciples (dualism), or God is both good and evil (monism) that is, God is the author of sin. Surely the cure is far worse than the disease. (p232)

“”””

the move to assimilate sin into a biological matrix faces daunting challenges. Christian biologism transforms human sin into a problem of biology.” But that places us on the horns of a christological dilemma: either Christ was fully human that is, participated fully in human biology-and therefore sinful; or, if Christ was not sinful, he lacked a nature in common with the rest of humanity (docetism). (p235)

“””””

In 1762, Rousseau opened his Social Contract with the immortal but indefensible line, “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” Rousseau affirmed “the natural goodness of man,” maintaining that human vices come from the outside, from the arts, sciences, government, and defective education To his detriment, he never plausibly explained how decent people consistently create indecent communities. (p253)

“”””

The Enlightenment essentially ignores human sinfulness. It believes human¿ty’s primary ethical principles are logically necessary and universally binding No society can flourish without rules that forbid murder, theft, and treachery. Rational people should see that it is best for all if everyone is good. Further, ordinary people can attain substantial goodness, both in good actions and in the capacity to choose the good, if they are mindful, know the rules, and heed germane counsel. (p255)

“”””

Adam’s sin, just as the Lord threatened, had death as its consequence (Gen. 2:17). 4 The universal consequences of Adam’s sin are emphasized, for his sin did not just affect himself; it introduced both sin and death into the world.’ Death must not be restricted to physical death here, for both physical and spiritual death are intended. (p272)

“””””

According to verse 13, sin was not reckoned to anyone’s account in the interval between Adam and Moses since there was no law. Nevertheless, we find in verse 14 that those who lived in this time period still died, even though they did not violate a law that was specifically revealed as Adam did. Here Murray proposes a brilliant solution. Why did they die if their sins were not reckoned to them? They died, says Murray, because of Adam’s sin, not their own. If their sin was not counted against them, then their death cannot be based on their own sin. They had to die for another reason. And the reason that is given is Adam’s sin. (p278)

“”””

in the naming exercise. Further, woman was created as a help to man. Thus we see an order of the man, the woman, and the animal. Chapter 3 shows us that that order is reversed in the temptation and sin. There the initiative flows from the animal to the woman to the man. (p293)

“”””

the philosopher Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716), a major proponent of the popular Enlightenment philosophy of optimism, according to which we are in the best of all possible worlds. Leibniz, who coined the term “theodicy,” believed that if there is evil in the world, it is a necessary part of the larger tapestry of God’s creation since God could not make anything second best. (p308)

Leave a comment