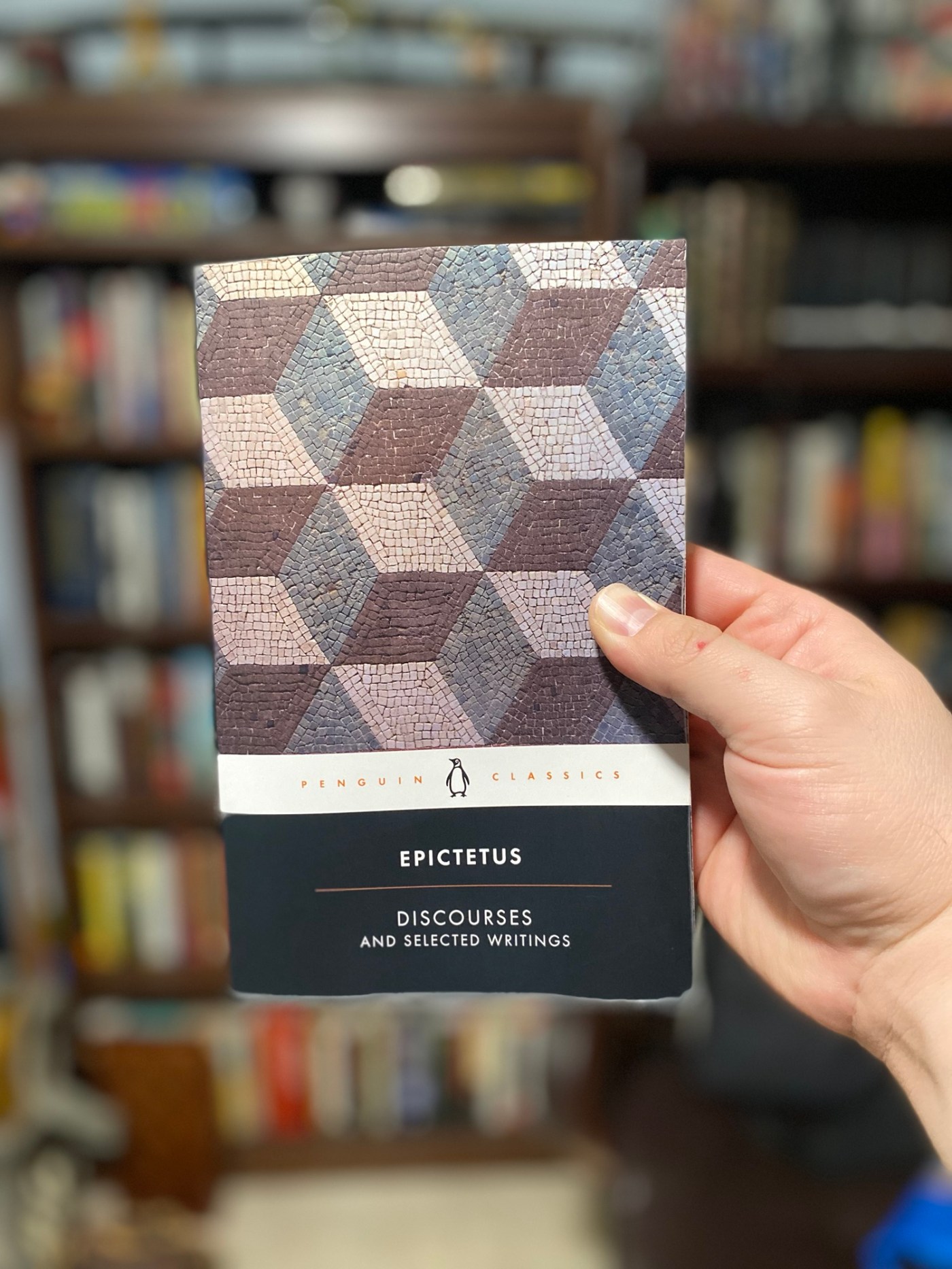

The book is Discourses by Epictetus. It was originally written down by a student of Epictetus around 108 AD. I read the Penguin Classics 2008 paperback edition. I read it in January of 2024.

The title refers to the conversations Epictetus had with his students to prove the points of his philosophy.

I read this because I want to read more stoic philosophy. Stoicism. provides practical insight in how to build fortitude against passions and impulses. Living in a time where everyone is led by passions and impulses, we need a little more stoicism to mitigate against that indulgent mindset.

Epictetus’ goal is to make a religious appeal to pure reason. I found this part very interesting. He claims that reason can account for itself.

“The faculty that analyses itself as well as the others, namely, the faculty of reason. Reason is unique among the faculties assigned to us in being able to evaluate itself what it is, what it is capable of, how valuable it is in addition to passing judgement on others.” (p5)

I’ve always spoken against this as an impossibility. If you ask someone why reason is the best source for the revelation of truth, they’ll appeal to the very thing in question and give you a bunch of reasons. This is circular reasoning and begging the question. An atheist will claim we ought not to do this but then do it when it comes to the sovereignty of pure reason. Epictetus is doing the same thing here.

My main takeaway from this book is how much it convicted me. It goes to show that God can use a crooked stick to draw straight lines. Because this stick is crooked in big ways but it still contains a lot of truth.

This is one such convicting passage.

“Even if I lack the talent, I will not abandon the effort on that account. Epictetus will not be better than Socrates. But if I am no worse, I am satisfied. I mean, I will never be Milo either; nevertheless, I don’t neglect my body. Nor will I be another Croesus and still, I don’t neglect my property. In short, we do not abandon any discipline for despair of ever being the best in it.” (p11)

I thought of this in terms of writing. I like writing , but I’ve read so much good literature, I feel like anything I ever wrote ever in my whole life would never be as good as McCarthy or Palahniuk or Steinbeck or Melville or any of my favorite authors. But that doesn’t mean I shouldn’t still do it. It is very difficult but I like it. So I should do it even if I lack the talent.

That’s an issue with me in many things. Sports, jobs, relationships. If I’m not naturally good at something I don’t even want to try it anymore. But that’s just not a good attitude to have. And the trouble is I think I’m naturally good at enough things that it determines my value in that thing. If I’m not good at something, then it’s stupid and a waste of time.

I was surprised to see the infinite regress being argued for in the superiority of reason above all things. Epictetus just dives right into the circular reasoning and presuppositions. Usually nowadays there is at least some pretending that that isn’t being done.

Epictetus definitely misses the mark in his presupposition of pure reason as the god of the system. And it’s ironic because he actually believed in the pagan Roman gods. But from his writings it’s clear his real lord is reason.

I would recommend this to lovers of philosophy. It was definitely approachable and readable. There is enough good in this book to be worth reading through the idolatry of reason that’s depicted. I might not recommend this to someone who believe everything they read. There is a lot of truth and someone who isn’t familiar with presuppositional apologetics might get swept away by Epictetus. But overall it’s a great book.

****************************************************

Notable Quotables

“”””

Even more than Musonius, Epictetus has a plain and practical agenda: he wants his students to make a clean break with received patterns of thinking and behaving, to reject popular morality and put conventional notions of good and bad behind them; in short, he aims to inspire in his readers something like a religious conversion, only not by appeal to any articles of faith or the promise of life in the hereafter (Stoics did not believe in the afterlife), but by appeal to reason alone. (Px)

“”””

The faculty that analyses itself as well as the others, namely, the faculty of reason. Reason is unique among the faculties assigned to us in being able to evaluate itself what it is, what it is capable of, how valuable it is in addition to passing judgement on others. (p5)

“”””

What should we have ready at hand in a situation like this? The knowledge of what is mine and what is not mine, what I can and cannot do. I must die. But must I die bawling? I must be put in chains but moaning and groaning too? I must be exiled; but is there anything to keep me from going with a smile, calm and self-composed? ‘Tell us your secrets.’ I refuse, as this is up to me.

‘I will put you in chains.’

What’s that you say, friend? It’s only my leg you will chain, not even God can conquer my will.’ (p7)

“”””

It is true, however, that no bull reaches maturity in an instant, nor do men become heroes overnight. We must endure a winter training, and can’t be dashing into situations for which we aren’t yet prepared. (p10)

“”””

Even if I lack the talent, I will not abandon the effort on that account. Epictetus will not be better than Socrates. But if I am no worse, I am satisfied. I mean, I will never be Milo either; nevertheless, I don’t neglect my body. Nor will I be another Croesus and still, I don’t neglect my property. In short, we do not abandon any discipline for despair of ever being the best in it. (p11)

“”””

But anyone whose sole passion is reading books, and who does little else besides, having moved here for this my advice for them is to go back home immediately and attend to business there, because they left home for nothing. (p14)

“”””

You have been given fortitude, courage and patience. Why should I worry about what happens if I am armed with the virtue of fortitude? (p18)

“”””

Is there anything of less utility than a beard? But nature has found a most becoming use even for that, enabling us to discriminate between the man and woman. Nature identifies itself even at a distance: ‘I am a man: come and deal with me on these terms. Nothing else is needed; just take note of nature’s signs.’ (p41)

“”””

Concerning the necessity of logic

Since reason is what analyses and coordinates everything, it should not go itself unanalysed. Then what will it be analysed by? Obviously by itself or something different. Now, this something different must either be reason or something superior to reason which is impossible, since there is nothing superior to reason. But if it is analysed by reason, what, in turn, will analyse that reason? Itself? If that’s the case, however, the first occurrence of reason could have done the same; whereas if another form of reason is required, the process will continue forever.

‘Yes, but in any case it is more important that we tend to our passions, and our opinions, and the like. (p42-43)

“”””

If God had made it possible for the fragment of his own being that he gave us to be hindered or coerced by anyone himself included then he wouldn’t be God, and wouldn’t be looking after us the way a god ought to. (p45)

“”””

Now, for what purpose did nature arm us with reason? To make the correct use of impressions. And what is reason if not a collection of individual impressions? Hence, it naturally comes to turn its analysis on itself. And what does the virtue of wisdom profess to investigate? Things good, bad and indifferent. And what is wisdom itself? Good. And ignorance? Bad. It is natural for wisdom too, then, to investigate itself, as well as its opposite.

Therefore, the first and most important duty of the philosopher is to test impressions, choosing between them and only deploying those that have passed the test. (p51)

“”””

Your duty is to prepare for death and imprisonment, torture and exile and all such evils with confidence, because you have faith in the one who has called on you to face them, having judged you worthy of the role. (p81)

“”””

If you want to be a man of honour and a man of your word, who is going to stop you? (p81)

“”””

Faced with external circumstances that we judge to be bad, we cannot help but be frightened and apprehensive. ‘Please, God,’ we say, ‘relieve me of my anxiety? Listen, stupid, you have hands, God gave them to you himself. You might as well get on your knees and pray that your nose won’t run. A better idea would be to wipe your nose and forgo the prayer. The point is, isn’t there anything God gave you for your present problem? You have the gifts of courage, fortitude and endurance. With ‘hands’ like these, do you still need somebody to help wipe your nose? (p113)

“”””

Well, you are no Heracles, with power to clear away the ills of other people; no, you are not even Theseus, otherwise you might at least relieve Attica of its troubles. Therefore, set your own house in order. Cast out of your mind not Procrustes or Sciron* but sorrow, fear, lust, envy, spite, greed, petulance and over-indulgence. Getting rid of these, too, requires looking to God for help, trusting him alone, and submitting to his direction. (p116)

“”””

you can’t hope to make progress in areas where you have made no application. (p117)

“”””

As a general rule, nature designed the mind to assent to what is true, dissent from what is false and suspend judgement in doubtful cases. Similarly, it conditioned the mind to desire what is good, to reject what is bad and to regard with indifference what is neither one nor the other. (p146)

“”””

Therefore, when you say, ‘Come and hear me lecture,’ be sure you have a purpose in lecturing. When you find your direction, check to make sure that it is the right one. Is your goal to educate or be praised? (p169)

“”””

By a process of logical elimination, the conclusion emerges that we will come through safely only by allying ourselves with God.

‘What do you mean, “allying ourselves”?’

Acting in such a way that, whatever God wants, we want too; and by inversion whatever he does not want, this we do not want either. How can we do this? By paying attention to the pattern of God’s purpose and design. (p186)

“”””

Freedom is not achieved by satisfying desire, but by eliminating it. (p195)

“”””

A book is an external, just like office or public honours. Why do you want to read anyway for the sake of amusement or mere erudition? Those are poor, fatuous pretexts. Reading should serve the goal of attaining peace; if it doesn’t make you peaceful, what good is it? (p198)

“”””

‘Isn’t reading a kind of preparation for life?’

But life is composed of things other than books, (p199)

“”””

If you want to make progress, put up with being perceived as ignorant or naive in worldly matters, don’t aspire to a reputation for sagacity. (p226)

“”””

Don’t let thoughts like the following disturb you: ‘I am going to live a life of no distinction, a nobody in complete obscurity.’ Is lack of distinction bad?* Because if it is, other people cannot be the cause of it, any more than they can be the cause of another’s disgrace. Is it solely at your discretion that you are elevated to office, or invited to a party? No; so it cannot be a dishonour if you are not. And how can you be ‘a nobody in obscurity’ when you only have to be somebody in the areas you control the areas, that is, where you have the ability to shine? (p230)

“”””

And avoid trying to be funny. That way vulgarity lies, and at the same time it’s likely to lower you in your friends’ estimation.

It is also not a good idea to venture on profanity. If it happens, and you aren’t out of line, you may even criticize a person who indulges in it. Otherwise, signal your dislike of his language by falling silent, showing unease or giving him a sharp look. (p238)

“”””

At a dinner party, for instance, don’t tell people the right way to eat, just eat the right way.

If conversation turns to a philosophical topic, keep silent for the most part, since you run the risk of spewing forth a lot of ill-digested information. If your silence is taken for ignorance, but it doesn’t upset you well, that’s the real sign that you have begun to be a philosopher. Sheep don’t bring their owners grass to prove to them how much they’ve eaten, they digest it inwardly and outwardly bring forth milk and wool. So don’t make a show of your philosophical learning to the uninitiated, show them by your actions what you have absorbed. (p242)

Leave a comment