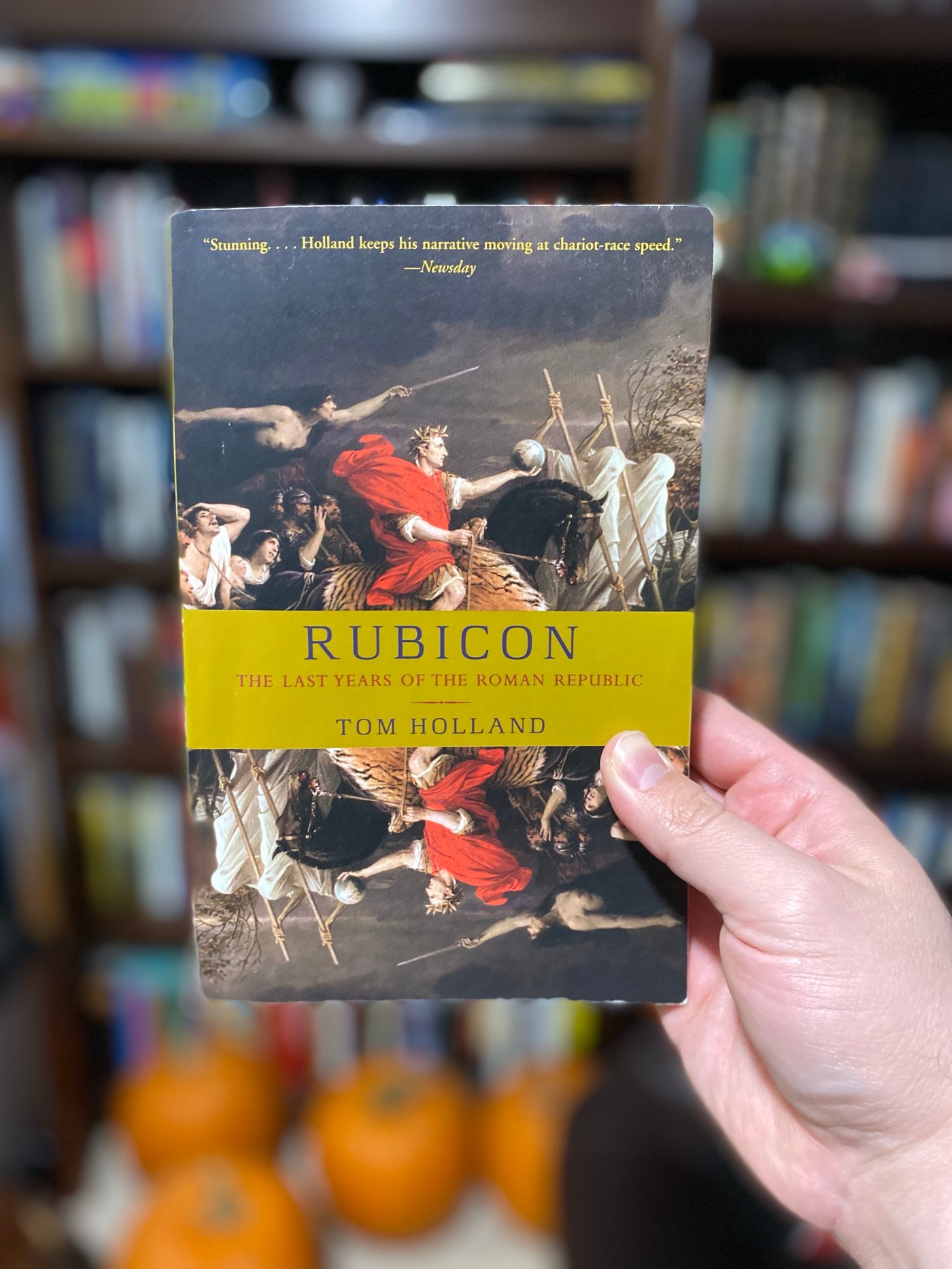

The book is Rubicon by Tom Holland. It was originally published in 2003 by Little Brown books. I read the Anchor Books paperback edition. I read it in October of 2023

The title refers to the Rubicon river that acted as the border between Italy and Gaul (France). Julius Caesar in 49 BC crossed the Rubicon with his army to march on Rome. This was bad because the military was not allowed in the city of Rome.

Armies were for distant campaigning for the expansion of the Roman empire. By crossing the Rubicon Caesar was crossing a point of no return. He was taking a gamble.

I read this because I want to read all of Tom Holland’s books. He’s my favorite historian. This is the first of his chronological Roman books, the end of the republic.

Holland writes about Julius Caesar and how the Roman republic fell. There were many reasons for this, and Holland explore all the nuances the last days of the republic.

He doesn’t make moral judgements either way on the right and wrong of anything that happened in history. He simply explains what happens and how.

My main takeaway is that systems of government are more fragile than we think. If things have been a certain way for a long time we tend to think they’ll always be like that. But things change.

It’s hardly ever one decisive moment by one man like crossing a little river, that changes the course of history. Holland understands this and goes into detail in all the players and wars that lead to the transition of Rome from a republic to an empire.

Another thing I took from learning about the romans is how unchristian it is. The idea of being a self-made man, picking yourself up by your bootstraps. That’s such an American and Roman mindset. But it’s not a Christian biblical mindset.

The Bible shows fathers passing things down to their sons as an inheritance. Patriarchy is about legacy.

The Romans had some of that but on a daily practical level, you had to make your own way. And that’s very much how American’s think. “Go west young man.” Carve out your own slice of the American dream.

There’s nothing particularly wrong with being self-made if you have to do that. But the key is we shouldn’t have to.

From the first believer Abraham, God said he would lead him to a place he will show him. God made promises of what he would give to our first patriarch, Abraham. He promised a lineage and a promised land.

Abraham didn’t have to, and indeed couldn’t, work to fulfill the promises himself. In fact, when he tried to take matters in his own hands with Hagar, it was a sin.

The model shown in the Bible is the Father giving an inheritance (the whole world) to his son Jesus, and we are co-heirs with Christ. Why shouldn’t we strive to do the same in our families?

This book made me think about the HBO series Rome. That’s such a great show as far as getting a feel for how daily life was in ancient Rome, and it goes over exactly the period Holland writes about. It also made me think about the Bible.

It’s weird to hear about people other than Jesus getting crucified. We churchify so much of ancient history, we forget that these things actually happened.

The Bible is real human history. We extract the reality out of Christianity when we separate the Bible from its historical context. We are way too ignorant of Christian and world history.

It surprised me that Romans did not get their Roman citizenship by birth.

“It was within the power of every father to reject a newborn child, to order unwanted sons, and especially daughters, to be exposed. Before the infant Caesar was breastfed, his father would first have had to hold him aloft, signaling that the boy had been accepted as his own and was therefore a Roman.” (p110)

Nothing was given. Everything was based on merit and accomplishments, and apparently if you didn’t appear to be strong or worthwhile even as a newborn baby, you would literally be thrown away out into the street like refuse for bulk pickup day. Usually tossed aside babies were swept up and put into slavery. A better outcome than death I guess.

The names and places definitely got confusing. Holland makes you pay attention, which I appreciate. He’s very detailed in his research and description of events and characters of history. You have to pay attention.

It was clear that the Romans took many things for granted. Things like the republic and nobility were just assumed to be cherished in the hearts of every human being.

Rome didn’t need a military guard because the threats were being taken care of by the campaigning armies. It didn’t enter their mind that one of their own generals could march on Rome and take over.

This meant there were no mitigating efforts against this happening. They took too many things for granted. Things were a certain way for so long they thought it would stay the same forever.

The tone was heroic but dark. A lot of political conspiracies and violent upheaval. Holland is a master at making history feel like a movie. He really places you in the time he’s writing about.

It’s hard to say Julius Caesar was a hero to emulate, just from his personal character. I believe he truly did have Rome’s best intentions in mind. And he was acting out his learned Roman identity in attaining as much power for himself as he could.

He was disciplined and determined. He knew what he wanted and went after it. All admirable qualities in a man. But he was very much a product of his time and maybe was led around too much by his dick.

The villain we should avoid is the Roman ideal of manhood. It cuts directly against the example we’re given in Jesus Christ.

I’d recommend this to lovers of ancient history, and to Christians to understand the atmosphere from which Christianity as a religion sprang forth. I’d also recommend this to any patriotic American who may be taking too much for granted.

****************************************************

Notable Quotables

“”””

Time and again he had hazarded his future and time and again he had emerged triumphant. This, to the Romans, was the very mark of a man. (xiv)

“”””

What was the Republic, after all, if not a partnership between Senate and people “Senatus Populusque Romanus,” SPQR (p36)

“”””

Everyone knew that Orientals were soft and fought like women. Even more inviting, everyone knew that the reason for this was because Orientals were obscenely rich. (p57)

“”””

in Rome a man was reckoned to be nothing without the fame that accrued from glorious deeds. (p62)

“”””

No citizen had ever led legions against their own city. To be the first to take such a step, and to outrage such a tradition, should have been a responsibility almost beyond a Roman’s enduring. Yet it seems that Sulla, far from wavering, betrayed not the slightest hesitation. (p67)

“”””

For all the trauma of Sulla’s march on Rome, no one could imagine that the Republic itself might be overthrown, because no one could conceive what might possibly replace it. (p74)

“”””

Until his [Sulla] own legions had broken the taboo in 88 bc the only men in arms ever to have entered the city had been citizens marching in triumphal parades. Otherwise, Rome had always been off-limits to the military. (p90)

“”””

It was no coincidence that the traditional ruling body of Rome, the Senate, derived its name from “senex” — “old man” — nor that senators liked to dignify themselves with the title of “Fathers.” (p102)

“”””

It was within the power of every father to reject a newborn child, to order unwanted sons, and especially daughters, to be exposed. Before the infant Caesar was breastfed, his father would first have had to hold him aloft, signaling that the boy had been accepted as his own and was therefore a Roman.

The Romans lacked a specific word for “baby,” reflecting their assumption that a child was never too young to be toughened up.

The deaths of children were constant factors of family life. Parents were encouraged to respond to such losses with flinty calm. The younger the child, the less emotion would be shown, so that it was a commonplace to argue that “if an infant dies in its cradle, then its death ought not even be mourned. (p110)

“”””

Marriage in Rome was a typically unsentimental business. Love was irrelevant, politics was all. (p115)

“”””

Nobility was perpetuated not by blood but by achievement. A nobleman’s life was a strenuous series of ordeals or it was nothing. (p121)

“”””

In childhood, boys would train their minds for the practice of law with the same single-minded intensity they brought to the training of their bodies for warfare. (p122)

“”””

The crippled or prematurely aged could expect to be cast aside, like diseased cattle or shattered wine jars. It hardly mattered to their masters whether they survived or starved. After all, as Roman agriculturalists liked to remind their readers, there was no point in wasting money on useless tools. (p143)

“”””

In an attempt to counteract Pompey’s glory-hogging he ordered all the prisoners he had captured to be crucified along the Appian Way. For more than a hundred miles, along Italy’s busiest road, a cross with the body of a slave nailed to it stood every forty yards, gruesome billboards advertising Crassus’s victory. (p146)

“”””

The Romans rarely went to war, not even against the most negligible foe, without somehow first convincing themselves that their preemptive strikes were defensive in nature. (p152)

“”””

Julius Caesar had been abducted while en route to Molon’s finishing school. When the pirates demanded a ransom of twenty talents, Caesar had indignantly claimed that he was worth at least fifty. He had also warned his captors that he would capture and crucify them once he had been released, a promise that he had duly fulfilled. (p164)

“”””

whenever the order of things had threatened to crack during the previous decades, rebellion had been signaled by a slave with a crown. Spartacus’s communism had been all the more unusual in that the leaders of previous slave revolts, virtually without exception, had aimed to raise thrones upon the corpses of their masters.

The royal pretensions of slaves fed naturally into the swirling undercurrents of the troubled age, the prophecies, which Mithridates’ propaganda had exploited so brilliantly, of the coming of a universal king, of a new world monarchy, and the doom of Rome. (p175)

“”””

Jerusalem was occupied. The Temple, despite desperate resistance, was stormed. Pompey, intrigued by reports of the Jews’ peculiar god, brushed aside the protests of the scandalized priests and passed into the Temple’s innermost sanctum. He was perplexed to find it empty. There can be little doubt as to who Pompey thought was more honored by this encounter, Jehovah or himself. Not wishing to aggravate the Jews any further, he left the Temple its treasures and Judaea a regime headed by a tame high priest. (p177)

“”””

The final, clinching disgrace, and the ultimate mark of a dangerous reprobate, was to be a good dancer. In the eyes of traditionalists nothing could be more scandalous. A city that indulged a dance culture was one on the point of catastrophe. (p188)

“”””

Gladiators, in the week before a fight, might need to have their foreskins fitted with metal bolts to infibulate them, but citizens were supposed to rely on self-control. To surrender to sensuality was to cease to be a man. (p190-191)

“”””

Laws and customs, precedents and myths, these formed the fabric of the Republic. No citizen could afford to behave as though they did not exist. To do so was to risk downfall and eternal shame. (p256)

“”””

Hence the Romans’ concern to refute all charges of bullying, and to insist that they had won their empire purely in self-defense. To people who had been flattened by the legions, this argument may have appeared laughable, but the Romans believed it all the same, and often with a deadly seriousness. (p261)

“”””

Enthusiasts for empire argued that Rome had a civilizing mission; that because her values and institutions were self-evidently superior to those of barbarians, she had a duty to propagate them; that only once the whole globe had been subjected to her rule could there be a universal peace. Morality had not merely caught up with the brute fact of imperial expansion, but wanted more. (p262-263)

“”””

It was well known that barbarians became more savage the farther north one traveled, indulging in any number of unspeakable habits, such as cannibalism, and even — repellently — the drinking of milk. (p266)

“”””

In Caesar’s energy there was something demonic and sublime. Touched by boldness, perseverance, and a yearning to be the best, it was the spirit of the Republic at its most inspiring and lethal. No wonder that his men worshiped him, for they too were Roman, and felt privileged to be sharing in their general’s great adventure. (p270)

“”””

The mood of the Republic was fretful, but not apocalyptic. Why would it have been otherwise? Rome’s system of government had endured for almost five hundred years.

A Roman could no more conceive of the Republic’s collapse than he could imagine himself an Egyptian or a Gaul. Fearful of the gods anger he may have been, but not to the point of dreading the impossible. (p286)

“”””

Hurrying in a carriage along dark and twisting byways, he finally caught up with his troops on the bank of the Rubicon. There was a moment’s dreadful hesitation, and then he was crossing its swollen waters into Italy, toward Rome. No one could know it at the time, but 460 years of the free Republic were being brought to an end. (p296)

“”””

This was why the legions of Gaul had been willing to cross the Rubicon. What, after nine years of campaigning, were the traditions of the distant Forum to them, compared to the camaraderie of the army camp? And what was the Republic, compared to their general? (p307)

“”””

“They complained that Pompey was addicted to command, and took pleasure in treating former consuls and praetors as though they were slaves.” So wrote his not unsympathetic adversary, who could give orders to his subordinates as he pleased and not be jeered at for it. But this was because Caesar, whatever he pretended otherwise, was not fighting as the champion of the Republic. Pompey was. (p310)

“”””

Without custom there could be no shame, and without shame anything became possible. A people whose traditions had withered would become prey to the most repellent and degrading habits. (p320-321)

“”””

Holding his [Brutus] bloodstained dagger proudly aloft, he headed for the Forum. There, in the people’s meeting place, he proclaimed the glad news: Caesar was dead; liberty was restored; the Republic was saved.

As though in derisory answer, from across the Campus came the sound of screams.

More distantly, the first wails of grief could be heard as Rome’s Jews began the mourning for the man who had always served as their patron. (p336-337)

“”””

Prince Aeneas, the grandson of Venus, the ancestor of the Julian clan, had fled burning Troy and voyaged with his small fleet to Italy, his quest, given him by Jupiter, to make a new beginning. It was from Aeneas and his Trojans that the Roman people had eventually sprung, and in their souls it could be imagined they still retained something of the wanderer. (p370)

Leave a comment