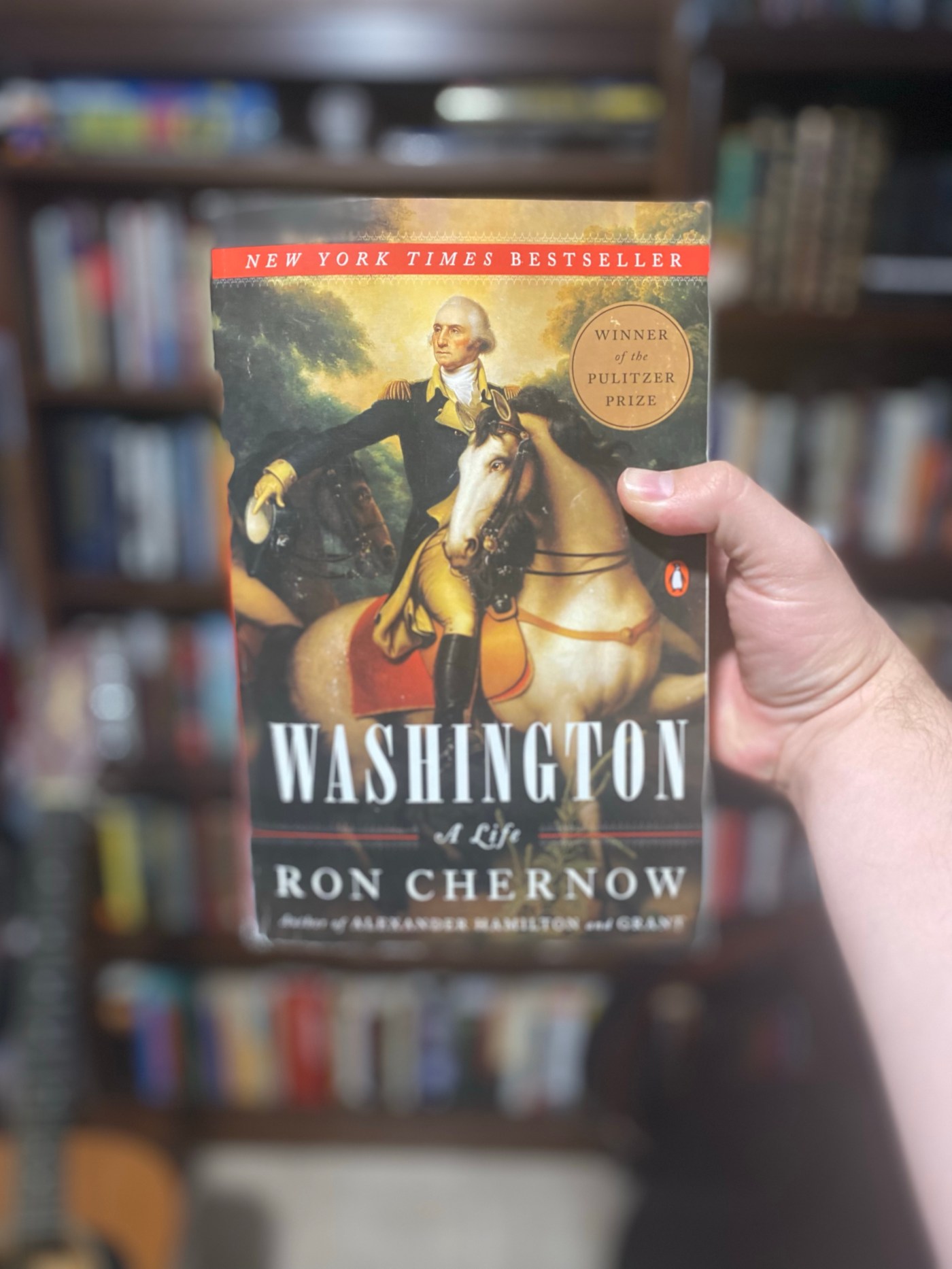

The book is Washington by Ron Chernow. It was originally published in 2010 by Penguin Books. I read the 2011 paperback edition. I read it in June of 2023.

The title obviously is from the subject of the biography, George Washington. The full title is Washington: A Life But Chernow takes advantage of the fact that the Washington name can stand on its own. And to call it “a life” speaks to Washington’s provincial aspirations.

This was in my biography category for my 2023 book round. I want to read more biographies. This is my second by Chernow. I’ve read his Hamilton biography. From what I’ve read, Ron Chernow is decidedly better than Walter Isaacson.

Chernow gives a detailed look George Washington and his historic life. Early family history, childhood, and his time in the French and Indian War all the way through to his presidency and death.

It’s a massive book. Washington is unique in how so much important history just evolves around him. He was the right man in the right place and time in a lot of ways.

All throughout there were points in his life where his decisions shaped the course of history. For example, he wanted to join the British Navy but his mother forbid it so he went into the Army, where he became a hero in the French and Indian War.

My main takeaway was how Washington won the hearts of those that followed him. He lead with gravitas. He’s the epitome of gravitas, weightiness. The men respected him so much because they saw firsthand his bravery and commitment to the cause of independence.

He lead by example. He sacrificed and risked so much and his soldiers saw it and they were proud to follow him.

So many things seemed to come together for Washington to be the right choice to be the first president.

One of the main factors was that he had no biological children and was most likely impotent. This assuaged fears in the founding fathers of any hereditary monarchy being set in place by Washington.

The most dramatic account of Washington’s bravery comes from more than one witness who saw him riding towards the enemy sword drawn while bullets flew through his open jacket and through his hat. He seemed to be immune to bullets.

“He displayed unblinking courage and a miraculous immunity in battle. When two horses were shot from under him, he dusted himself off and mounted the horses of dead riders. One account claimed that he was so spent from his recent illness that he had to be lifted onto his second charger. By the end, despite four bullets having torn through his hat and uniform, he managed to emerge unscathed.” (p59)

It got a little confusing keeping track of all the American and British generals. This is more from my inability to remember. Chernow is a clear writer, but there was just so much information to keep up with in this 800 page tome.

I learned that Washington never chopped down a cherry tree, and he didn’t have wooden teeth. He did lose all but one tooth and his dentures looked so gross that they looked like old dried wood.

This was a fantastic book. Well deserving of its Pulitzer Prize. It was very long (817 pages) and will challenge the casual reader. I would highly recommend it to lovers of biographies, American history and fans of the Hamilton musical.

****************************************************

Notable Quotables

With Washington, trust had to be earned slowly, and he balked at instant familiarity with people. (prelude pxx)

The pay issue carried tremendous symbolic weight for the striving, hypersensitive Washington, who chafed at anything pertaining to inferior salary and status. (p41)

Washington had led by example and exposed himself unflinchingly to enormous risk. “I fortunately escaped without a wound, though the right wing where I stood was exposed to and received all the enemy’s fire and was the part where the man was killed and the rest wounded.” He also engaged in some youthful boasting. “I can with truth assure you, I heard bullets whistle and believe me there was something charming in the sound.” (p44)

With unflagging resolution, he had kept his composure in battle, even when surrounded by piles of corpses. He had a professional a toughness and never seemed to gag at bloodshed; a born soldier, he was curiously at home with bullets whizzing about him. (p49)

He displayed unblinking courage and a miraculous immunity in battle. When two horses were shot from under him, he dusted himself off and mounted the horses of dead riders. One account claimed that he was so spent from his recent illness that he had to be lifted onto his second charger. By the end, despite four bullets having torn through his hat and uniform, he managed to emerge unscathed. (p59)

Washington speculated that he was still alive “by the miraculous care of Providence that protected me beyond all human expectation. I had 4 bullets through my coat and two horses shot under and yet escaped unhurt.?” In a stupendous stroke of prophecy, a Presbyterian minister, Samuel Davies, predicted that the “heroic youth Col. Washington” was being groomed by God for higher things. “I cannot but hope Providence has hitherto preserved [him] in so signal a manner for some important service to his country.” (p62)

There was a gravitas about the young Washington, a seriousness of purpose and a fierce determination to succeed, that made him stand out in any crowd. (p69)

That he wasn’t a biological father made it easier for him to be the allegorical father of a nation. It also retired any fears, when he was president, that the nation might revert to a monarchy, because he could have no interest in a hereditary crown. (p104)

Once again, he was a diligent boss, not a gentleman farmer. Each day he rode twenty miles on horseback and personally supervised field work, fence construction, ditch drainage, tree planting, and dozens of other activities. An active presence, he liked to demonstrate how things should be done, leading by example. One startled visitor expressed amazement that the master “often works with his men himself, strips off his coat and labors like a common man.” (p119)

Washington couldn’t bear anything slovenly. “I shall begrudge no reasonable expense that will contribute to the improvement and neatness of my farms, for nothing pleases me better than to see them in good order and everything trim, handsome, and thriving about them,” he advised one estate manager. “Nor nothing hurts me more than to find them otherwise and the tools and implements laying wherever they were last used, exposed to injuries from rain, sun, etc.” No detail was too trivial to escape his notice, and he often spouted the Scottish adage “Many mickles make a muckle— that is, tiny things add up. (p119)

Bishop William White of Pennsylvania, Washington’s pastor during his presidency in Philadelphia, also stated, “I do not believe that any degree of recollection will bring to my mind any fact which would prove General Washington to have been a believer in the Christian revelation.” (p130)

However ecumenical in his approach to religion, Washington never doubted its signal importance in a republic, regarding it as the basis of morality and the foundation of any well-ordered polity. “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports,” he declared in his farewell address. (p133)

Unlike the French Revolution, the American Revolution started with a series of measured protests by men schooled in self-government, a long, exhaustive search for a diplomatic solution, before moving toward open rebellion. (p145)

Still more jarring was a ruling from London that land grants to French and Indian War veterans under the 1763 proclamation would be limited to British regulars, discriminating against colonial officers and reopening an ancient wound for Washington. “I conceive the services of a provincial officer as worthy of reward as a regular one and [it] can only be withheld from him with injustice,” he observed with contempt. As we have seen, the ambitious Washington took these slights personally, and they now tipped him over the edge into open revolt. (p167)

Many southerners feared that the New Englanders were a rash, obstinate people, and worried that an army led by a New England general might someday turn despotic and conquer the South. The appointment of George Washington would soothe such fears and form a perfect political compromise between North and South. (p185)

Finally he was stranded alone on the battlefield with his aides, his troops having fled in fright. Most astonishingly, Washington on horseback stared frozen as fifty British soldiers started to dash toward him from eighty yards away. Seeing his strangely catatonic state, his aides rode up beside him, grabbed the reins of his horse, and hustled him out of danger.

In this bizarre conduct, Nathanael Greene saw a suicidal impulse, contending that Washington was “so vexed at the infamous conduct of his troops that he sought death rather than life.”

Only with difficulty did Washington’s colleagues “get him to quit the field, so great was his emotions.” It was a moment unlike any other in Washington’s career, a fleeting emotional breakdown amid battle. (p254)

When the fusillade of bullets ended and the enemy scattered, Fitzgerald finally peeked and saw Washington, untouched, sitting proudly atop his horse, wreathed by eddying smoke.

Fitzgerald said “Thank God, your Excellency is safe!” Fitzgerald said to him, almost weeping with relief. Washington, unfazed, took his hand fondly. “Away, my dear colonel, and bring up the troops. The day is our own!”

Fitzgerald wasn’t the only one bowled over by Washington’s coolness. “I shall never forget what I felt when I saw him brave all the dangers of the field and his important life hanging as it were by a single hair with a thousand deaths flying around him,” wrote a young Philadelphia officer. “Believe me, I thought not of myself.” (p282)

As in previous battles, Washington experienced narrow escapes. While he was deep in conversation with one officer, a cannonball exploded at his horse’s feet, flinging dirt in his face; Washington kept talking as if nothing had happened. (p343)

Standing on elevated ground, Washington watched the dramatic scene with Generals Lincoln and Knox. “Sir, you are too much exposed here,” urged Washington’s aide David Cobb, Jr. “Had you not better step a little back?” “Colonel Cobb,” Washington said coolly, “if you are afraid you have liberty to step back.” (p415)

To reassure the men of congressional good faith, he read aloud a letter from Congressman Joseph Jones of Virginia and tripped over the first few sentences because he couldn’t discern the words.

Then he pulled out his new spectacles, shocking his fellow officers: they had never seen him wearing glasses. “Gentlemen, you must pardon me,” he said. “I have grown gray in your service and now find myself growing blind.” These poignant words exerted a powerful influence.

The disarming gesture of putting on the glasses moved the officers to tears as they recalled the legendary sacrifices he had made for his country. When he left the hall moments later, the threatened mutiny had ended, and his victory was complete. (p435-436)

One day the king [George III] asked West whether Washington would be head of the army or head of state when the war ended. When West replied that Washington’s sole ambition was to return to his estate, the thunderstruck king declared, “If he does that, he will be the greatest man in the world.” (p454)

At war’s end, he stood alone at the pinnacle of power, but he never became drunk with that influence, as had so many generals before him, and treated his commission as a public trust to be returned as soon as possible to the people’s representatives. Throughout history victorious generals had sought to parlay their fame into political power, whereas Washington had only a craving for privacy. Instead of glorying in his might, he feared its terrible weight and potential misuse. (p457)

In 1788 he wrote that “the life of a husbandman, of all others, is the most delectable … To see plants rise from the earth and flourish by the superior skill and bounty of the laborer fills a contemplative mind with ideas which are more easy to be conceived than expressed.” Many dinner guests noted that Washington’s flagging attention perked up whenever agriculture was discussed. (p482)

I can only say that there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it [slavery], but there is only one proper and effectual mode by which it can be accomplished, and that by legislative authority. (p490)

Casting their votes on February 4, 1789, they vindicated Lee’s prediction: all 69 electors voted for Washington, making him the only president in American history to win unanimously. (p551)

With an excellent memory for names, Washington seldom required a second introduction. In a manner that reminded some of European kings, Washington never shook hands, holding on to a sword or a hat to avoid direct contact with people. (p577)

He excelled as a leader precisely because he was able to choose and orchestrate bright, strong personalities. (p596)

In fact, virtually all of the founders, despite their dislike of slavery, enlisted in this conspiracy of silence, taking the convenient path of deferring action to a later generation. (p623)

His failure to use the presidency as a bully pulpit to air his opposition to slavery remains a blemish on his record. He continued to fall back on the self-serving fantasy that slavery would fade away in future years. The public had no idea how much he wrestled inwardly with the issue. (p624)

The dentures that Greenwood fashioned during Washington’s first year as president used natural teeth, inserted into a framework of hippopotamus ivory and anchored on Washington’s one surviving tooth. Some dental historians have argued that these dentures were forged from walrus or elephant ivory; the one thing they were not made from is the wood so powerfully entrenched in popular mythology. (p642)

It was also a decisive moment legally for Washington, who had felt more bound than Hamilton by the literal words of the Constitution. With this stroke, he endorsed an expansive view of the presidency and made the Constitution a living, open-ended document. The importance of his decision is hard to overstate, for had Washington rigidly adhered to the letter of the Constitution, the federal government might have been stillborn. (p650)

Thomas Jefferson seemed unfazed by the regicide and the large-scale massacres preceding it. “My own affections have been deeply wounded by some of the martyrs to this cause,” he conceded, then added cold-bloodedly, “but rather than it should have failed, I would have seen half the earth desolated. Were there but an Adam and Eve left in every country, and left free, it would be better than it is now.” (p689)

That the Washingtons faulted Judge [runaway slave] for “ingratitude” and pretended that she was like a daughter again shows the moral blindness of even comparatively enlightened slave owners. Judge’s flight belied whatever sedative fantasies the Washingtons might have had that slaves developed familial relations with their masters, transcending the indignity of bondage. (p761)

At a time when black education was feared as a threat to white supremacy, Washington ordered that the young slaves, before being freed, should “be taught to read and write and to be brought up to some useful occupation.” He also provided a fund to care for slaves too sick or aged to enjoy the sudden fruits of freedom. (p802)

Leave a comment