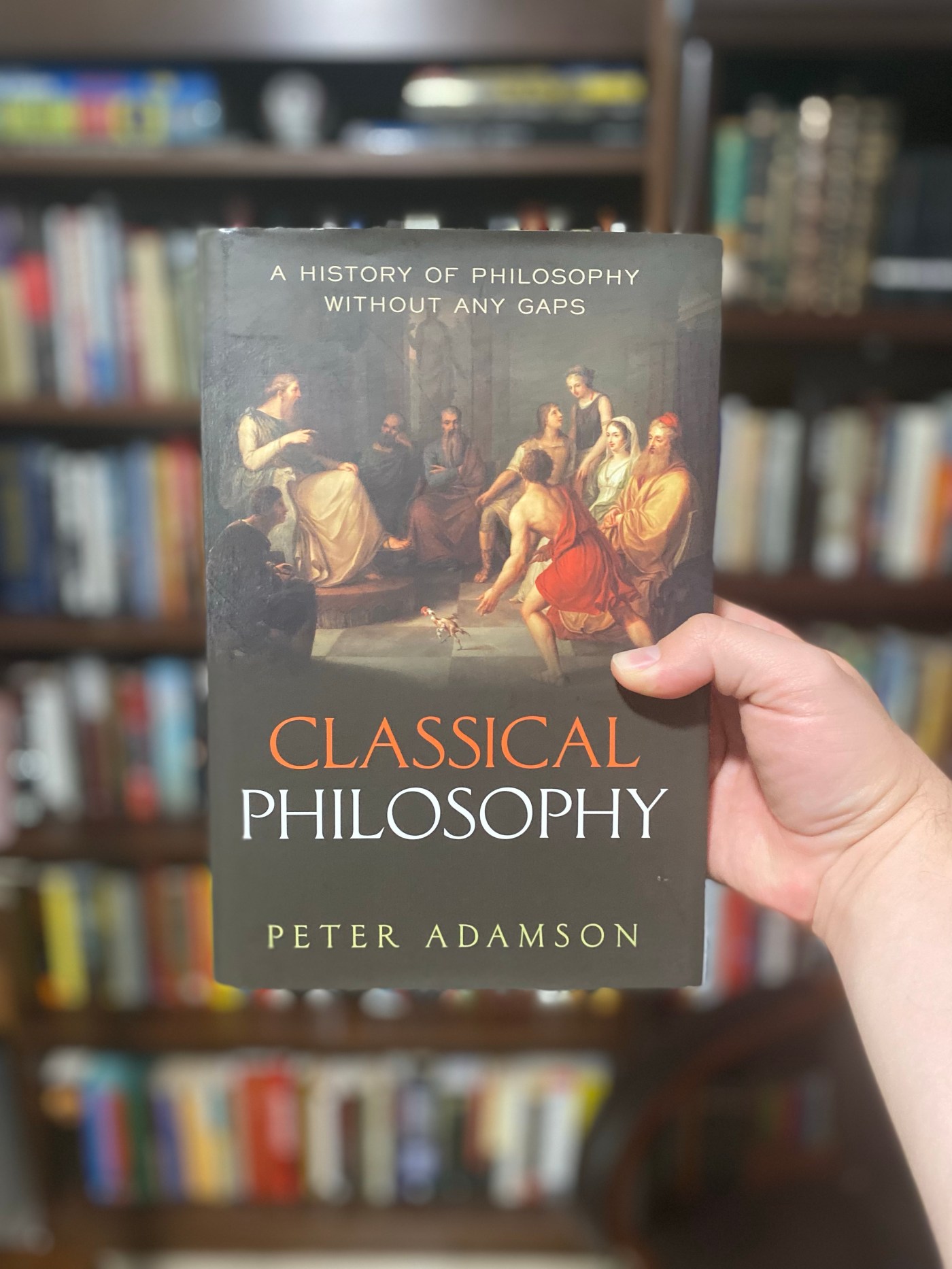

The book is Classical Philosophy by Peter Adamson. It was originally published in 2014 by Oxford University Press. I read the first edition. I read it in May of 2023.

This is the first book in a series called A History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps. This volume is a survey of the presocratic philosophers as well as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. The beginnings of philosophy as a practice.

I read this because I want to learn more about philosophy. I plan to read the rest of the series. It’s also a podcast so maybe I’ll listen to that.

I like origin stories. I like to know how ideas started or where they come from. Pythagoras introduced the idea of reincarnation where the soul can leave the body. And this lead to Dualism, the idea that the soul and body are separate. This then of course leads to Gnosticism, the idea that the soul must escape the body and everything spiritual is above and better than everything natural. It’s interesting to find the throughline that connects all these views.

Protagoras introduced the idea of relativism with this line “man is the measure of all things, of the things that are, that they are, of the things that are not, that they are not.” This is the matchstick that lit countless fires of nonsense throughout the world. Relativism is the most absurd idea that Satan ever planted in human minds. It’s a view that by its nature contradicts itself and no one sees it.

A lot of my main takeaways from this book are lists of other books to read. One of those books is Theogony by Hesiod. It’s the ancient account of the origins of the Greek gods. This sounds like good prep reading since I’m about to read The Iliad and The Odyssey for the first time.

After taking a little peak into the minds of ancient philosophers, it makes me very grateful to be a Christian. I really appreciate the light that Christ brought to a dark world. Even a great thinker of the time like Plato envisioned a perfect society that included slavery and totalitarian rule. This book makes it clear how Christ truly changed the world when he came.

I liked Aristotle’s search for meaning and purpose.

“Is it really obvious, though, that all humans share some purpose or function? Aristotle answers that question with a question of his own: how could it be that the parts of my body, like my eyes, have a function, without my having a function?” (p266)

Aristotle doesn’t ignore or contradict the obvious world around him when he comes to his conclusions.

The names and timelines got a little confusing. I wasn’t always sure if I was pronouncing the Greek names correctly.

Adamson is a good writer. This is a dense subject but he kept it clear and very accessible. Easy to read and follow along. I couldn’t detect any political or worldview bias from Adamson in his presentation of these philosophies. He keeps the history fair and objective.

I’d recommend this to lovers of history and philosophy. It’s not very long (316p) or difficult to read. I look forward to reading the rest of the series.

****************************************************

Notable Quotables

Theogony, which as its title says is a poem about the generation or birth of the gods.? After a long opening prayer to the Muses, Hesiod tells us that the first of all things to come into being was the god Chaos, who seems to represent

underworld. Then comes Gaia. Gaia is the earth, and she gives birth to the god Ouranos, some kind of void or gap between the earth and the which means “heaven.” They mate to produce a whole generation of gods, including Zeus’ father, Kronos. This is a theme commonly found in other early religions: the mating of the earth and heaven which produces other cosmic principles. (p18)

But this theory of reincarnation at least relates to, and maybe even inaugurates, a philosophical theory with a grand lineage: dualism. Dualism is simply the view that the soul and the body are two distinct things. (p28)

This might remind us of Xenophanes, who attacked Homer and Hesiod for making the gods too much like humans, with human emotions and irrationality. Xenophanes, like the author of The Sacred Disease, saw rationality as the correct religious attitude, not as a complete departure from religion. (p72)

But if you remember just one thing about Protagoras, don’t remember that story. Remember his famous remark that “man is the measure of all things, of the things that are, that they are, of the things that are not, that they are not.” In this brief statement we have the roots of an ancient and, to many, disturbing philosophical tradition: relativism. (p81)

his divine sign. Plato confirms Xenophon’s report that Socrates could hear a divine voice, which would speak up and warn him against those actions which would be wrong (Apology 31d). Socrates, then, was given a way to cheat his way to virtue. (p101)

Whenever you’re presented with a bold new theory, ask whether the theory is consistent with itself. For example, if someone says that nothing is true, you can ask him whether this claim is itself true. Or if someone says that language is meaningless, you can ask her how she is able to convey this idea in a sentence. In the same way, Socrates suggests that Protagoras’ relativism doctrine is self-refuting. For, even if Protagoras agrees with the doctrine, Socrates does not. Thus it will be true for Socrates that Protagoras’ doctrine is false. (p133)

This is the origin of the infamous class system of Plato’s Republic, since it sets up a division of the city into two types of people, the guardian soldiers and the laborers. The guardians will rule over the craftsmen, and their rule will, as we’ll see shortly, be absolute and unquestioned. This aspect of the Republic has come in for its share of criticism. Famously, the twentieth-century philosopher Karl Popper accused Plato of being an enemy of what he called “the open society, and saw the a Republic as a founding text of totalitarianism. (p148)

To put it bluntly: Aristotle invented logic. We now take it for granted that philosophy involves, and even presupposes, logic. (p213)

Aristotle wants us to see that we can’t understand or explain things without invoking their form and matter as well as their efficient causes. Talking about pushers and pullers will only get us so far. (p239)

What happens for the most part is that purposes are pursued and achieved: final causes do their work. Occasionally, but only occasionally, a desirable result is achieved without being pursued, without any final cause being involved. And that is what we call chance or luck. How, then, could everything in nature be like this, since the whole point of luck is to be exceptional, whereas nature is just what almost always happens. (p241)

What are we, as it were, designed to do? If we do have some purpose, then surely the good life will be the life in which that purpose is fulfilled to the greatest extent possible. Just as being good flute-player will consist in playing the flute well, so being a good human will consist in doing whatever humans are supposed to do, and performing that function well.

Is it really obvious, though, that all humans share some purpose or function? Aristotle answers that question with a question of his own: how could it be that the parts of my body, like my eyes, have a function, without my having a function? (p266)

Leave a comment